What looked like a routine corporate slowdown in Ontario just turned into a political and economic thunderclap — and it’s sending a message far beyond one factory floor.

Canadian officials have moved to reduce tariff relief (effectively shrinking tariff-free import privileges) for General Motors, after GM ended production of its BrightDrop electric delivery vans in Ingersoll, Ontario. In plain terms: Canada is saying, you don’t get the perks if you don’t keep the promises.

The shock isn’t just that Canada acted — it’s how directly it acted. Rather than firing off another angry press conference or threatening future retaliation, Ottawa reached for a tool that companies understand instantly: access to cheaper imports. Under Canada’s approach, automakers can receive tariff exemptions, but those benefits are tied to job and investment commitments. When production disappears, the benefits can disappear too. And GM just found that out the hard way.

According to reporting, Canada is cutting GM’s tariff-free import quota by 24% — a concrete penalty that can’t be spun away as “politics” or waved off as “temporary.”

Here’s why the Ingersoll moment is suddenly a continental story: it’s unfolding against a backdrop of renewed U.S.–Canada tariff pressure under President Donald Trump. In July 2025, the White House said Trump signed an executive order raising tariffs on Canadian goods from 25% to 35%, adding more heat to an already brittle relationship.

So while Washington leans on broad tariffs, Canada is answering with something sharper: conditional privileges. Not “we might retaliate,” but “you’re losing this benefit now.”

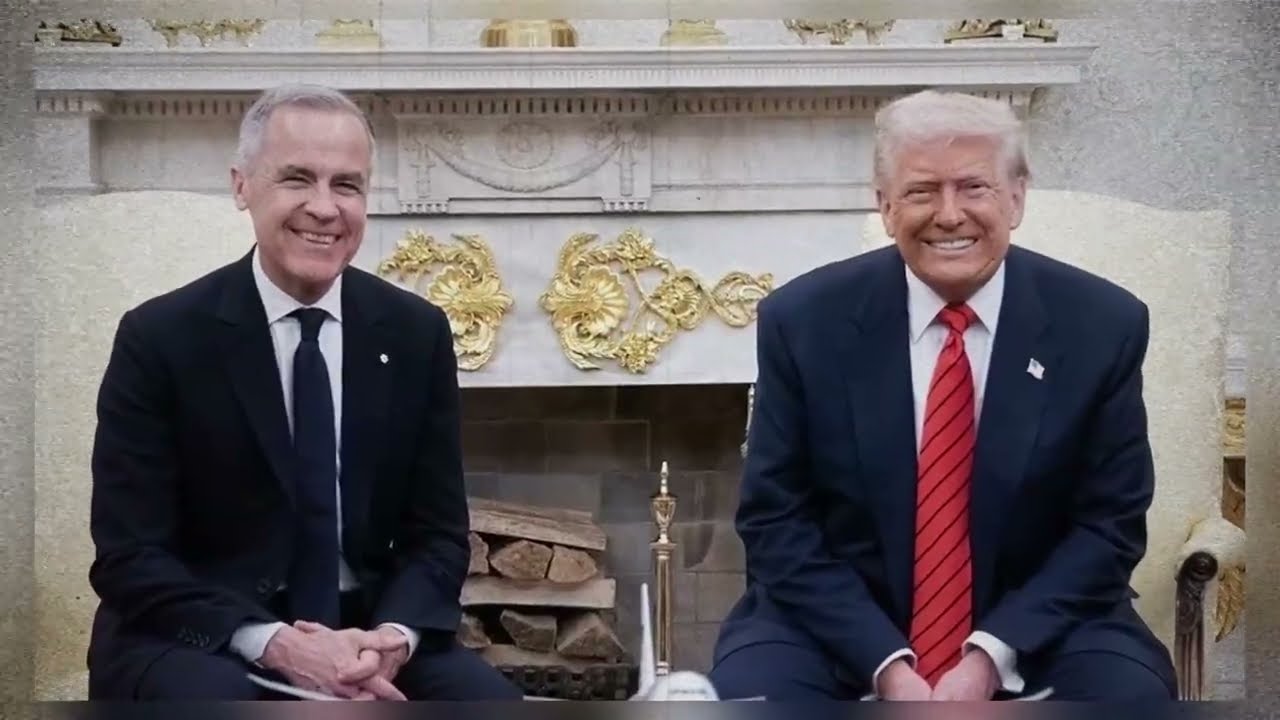

And the politics are just as intense as the economics. Prime Minister Mark Carney has framed the auto sector as a national pillar — with major employment stakes — and this move signals that Canada is willing to enforce commitments even when the target is a giant like GM.

What makes this especially unnerving for boardrooms is the precedent: if a government can tie incentives and tariff relief to measurable behavior — and then actually enforce it — “flexibility” stops being a corporate superpower and becomes a liability. A company can pivot supply chains and product lines, but it can’t pivot away from a policy framework that’s designed like a contract.

Meanwhile, the broader U.S.–Canada relationship is still in flux. Carney has also made tactical concessions in the wider tariff standoff to keep negotiations moving — a sign that the diplomatic channel remains open even as the industrial policy hammer is coming down.

The result is a new kind of North American pressure cooker:

Tariffs that can change fast and hit wide.

Targeted exemptions that can be withdrawn surgically and hurt specific companies immediately.

And communities — like Ingersoll — caught at the center of decisions made in distant political rooms and corporate headquarters.

For everyday people, this isn’t abstract. It lands in the real world as job uncertainty, supplier whiplash, and the creeping fear that “industrial strategy” is just another phrase for your town being the one that takes the hit first.

And for GM? Canada’s message is blunt: If you want the benefits of building here, you have to actually build here.