Canada’s fighter-jet debate just got a lot louder—and for the first time in years, the F-35 doesn’t look like a “done deal.”

Because Ottawa isn’t arguing about stealth anymore.

It’s arguing about sovereignty, jobs, and who controls the keys to Canada’s defense future.

“We didn’t get enough”—Joly puts the F-35 on notice

In the transcript, Industry Minister Mélanie Joly makes a blunt claim: Canada has been in the F-35 ecosystem for decades, has put serious money into the program, and yet the industrial payoff has been underwhelming.

Not symbolic participation. Not “a few contracts.”

Real domestic benefit. Real leverage. Real capacity.

The subtext is unmistakable: if Canada is paying billions, Canadians expect more than crumbs.

And that’s where the alternative arrives—fast and loud.

Saab’s offer: 10,000 jobs and a “Made in Canada” fighter line

Sweden’s Saab steps in with a proposal designed to hit Ottawa’s pressure points:

a Gripen E production line in Canada

10,000 high-tech jobs

broad technology transfer

a domestic supplier and maintenance ecosystem that keeps expertise—and money—inside Canada

This isn’t just “buy our jet.” It’s “build a national aerospace engine around it.”

And politically, that changes everything.

Because now the question isn’t “Which fighter is best?”

It’s: Do we want to own our capability, or rent it?

The mission mismatch problem

The transcript draws a sharp contrast in mission philosophy:

The F-35 is described as a fifth-gen, stealth-centric platform optimized for deep-strike and high-end alliance integration.

Canada’s daily reality, however, is framed as Arctic defense, long-range patrol, readiness in extreme conditions—less “expeditionary stealth raids,” more “protect the largest territorial airspace on Earth.”

That’s the uncomfortable question hanging over the procurement:

Are we buying the jet that wins NATO’s hardest fight… or the jet that best matches Canada’s most likely fight?

The cost argument that won’t go away

The transcript also leans into a brutal readiness metric: cost per flight hour.

It claims:

Gripen E: ~$8,000 per flight hour

F-35: ~$35,000–$47,000 per flight hour

Whether those exact numbers hold in every accounting method or not, the argument is clear:

Lower operating cost means:

more training hours

higher sortie rates

less time grounded by maintenance budgets

In other words: a fleet you can actually afford to fly.

The real red line: software and permission

Then comes the part that makes this bigger than procurement:

control.

The transcript describes the F-35 as a closed ecosystem where updates, sensitive repairs, weapons integration, and major upgrades funnel through U.S.-controlled channels. That’s not just logistics—it’s dependency.

Gripen, by contrast, is framed as open-architecture and integration-friendly, enabling domestic innovation and non-U.S. systems integration—more freedom to tailor the jet to national needs.

So the tradeoff becomes stark:

F-35 = unmatched stealth + alliance standardization, but tighter gatekeeping

Gripen = flexibility + domestic control, but potential interoperability friction

Washington’s pressure: interoperability as leverage

The transcript doesn’t sugarcoat what the U.S. is thought to be signaling: the F-35 isn’t merely a plane—it’s an alliance lock-in mechanism.

A shared platform simplifies:

data sharing

joint targeting

coalition support

If Canada exits, it’s not just “Canada bought a different jet.”

It becomes a precedent: a close ally stepping outside the U.S. defense orbit.

And Washington notices precedents.

The twist: Canada is diversifying on purpose

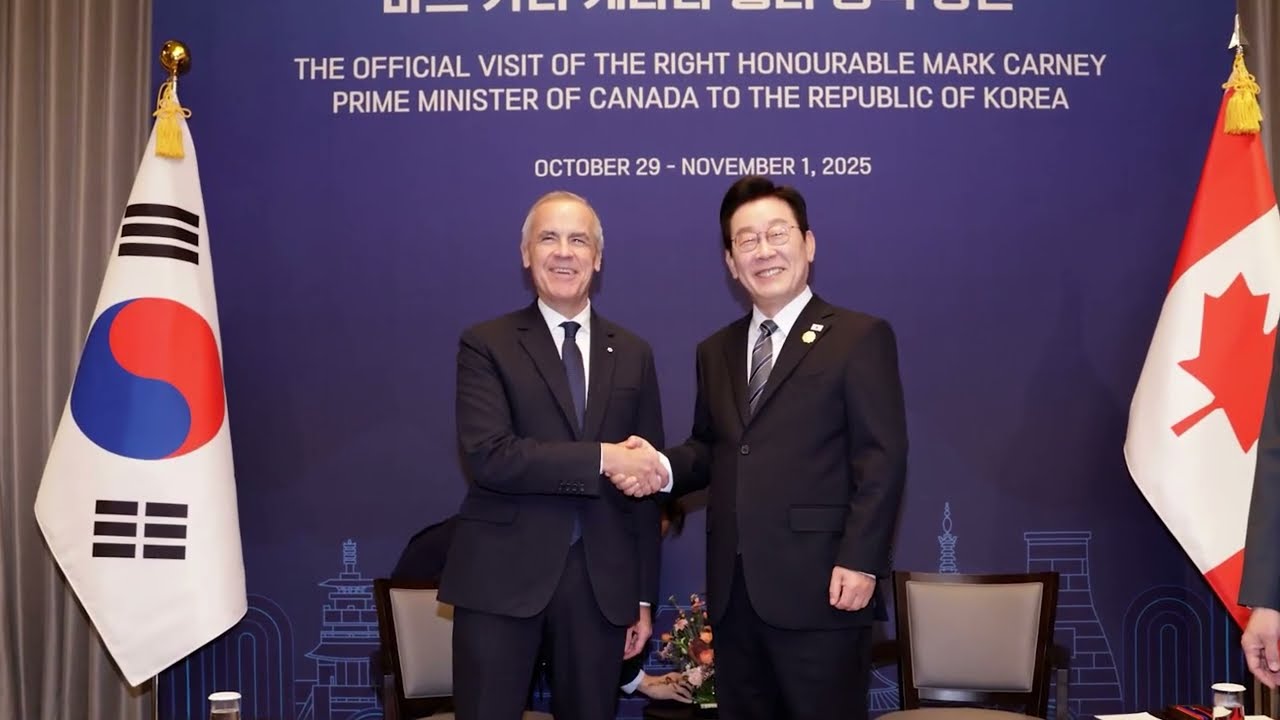

The transcript frames this as part of a larger Carney-era strategy: reduce single-axis dependency and build manufacturing power at home.

It cites a new defense cooperation agreement with South Korea (dated October 30, 2025 in the transcript) as evidence Canada is widening its partner network—defense, tech transfer, and industrial collaboration beyond Washington.

That matters because it signals intent:

Canada isn’t just shopping for a fighter.

Canada is trying to rewire its economic and defense supply chains.

What this really is

This isn’t a single procurement controversy.

It’s a referendum on the next 30 years of Canadian power:

Do we maximize alliance integration, even if it means permanent dependence on U.S. systems?

Or do we trade some standardization for a domestic industrial base and greater autonomy?

And looming over it all is the question no government wants to answer out loud:

Can a mid-sized power truly be strategically independent… or does it just pick which dependency it prefers?